There’s an iconic house, on a little hill, in the center of the state of Virginia. A place where history was made, tragedy struck, and triumph prevailed. It’s beauty, its architecture a masterpiece.

As a child, we did a family vacation where we visited the Presidents of the United States homes. The one I remember most, Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello (Pronounced “Mon-ti-chel-lo”). I have had a little more than three decades to shape my thoughts, explore my ideas, love my country and pursue happiness.

Today, I took my children to the home on the “little hill” in Charlottesville, Virginia and challenged them to pursue their own path, but reflect on the great people and courage that gave them the opportunity.

We opt to walk the path that leads to the place on the hill that holds more than beauty and history; it captures the man who Thomas Jefferson was.

A house is so magnificent that it etches itself deep in the memories of my childhood. A project that became almost a lifelong obsession with Jefferson bankrupted his family and stood as one of America’s most iconic and significant architectural creations.

It’s saying a lot about a structure, and it says a lot about the man the American people elected as our third President of the United States.

A man who pursued many passions. He was a political philosopher, an archaeologist, musician, botanist, and enjoyed bird watching. Not just passions of his–he was successful in all. So successful that at a dinner honoring 49 American Nobel Prize winners, John F. Kennedy famously quipped,

“I think that this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.”

We buy our tickets to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello (I recommend buying online and in advance, to save time) and head up to the trail.

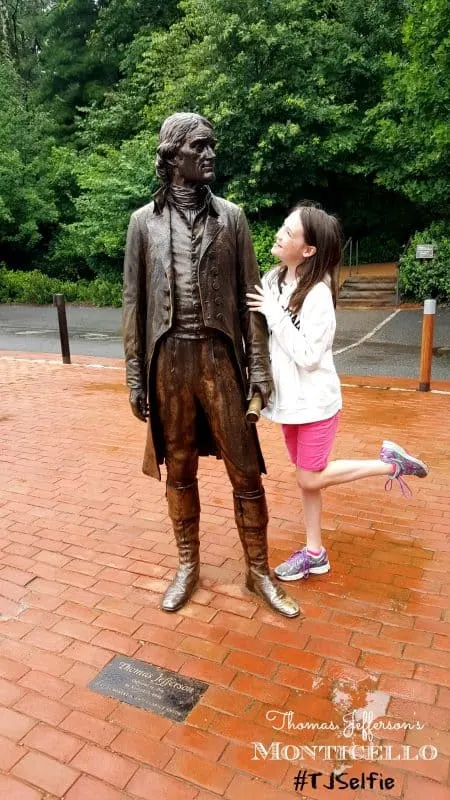

At the top of the stairs, where you meet the shuttle, there is a statue of Thomas Jefferson. You are encouraged to take a #TJSelfie. Miss M was up for it.

This full-length sculpture of Thomas Jefferson is the work of designer and sculptor Ivan Schwartz, whose company, StudioEIS, is located in Brooklyn, NY.

There is no hiding from the Virginia humidity. It coats us with a sticky mist as we enter the gravel covered trail. The path is wide enough for people both coming and going, and though the brochure refers to it as gravel, I find it more to be like sand found on a beach where the shells crash and tumble.

The trail is a pleasant walk, though mostly uphill at a slight grade, it winds 0.35 miles to our first stop.

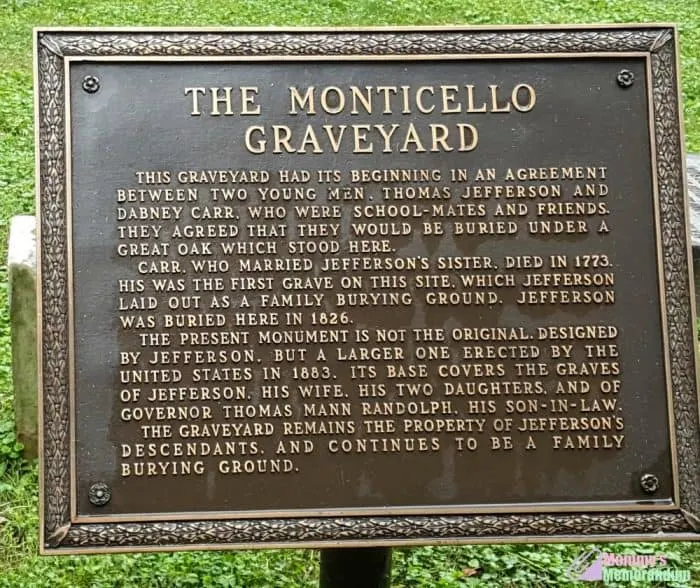

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello Family Cemetery

The Thomas Jefferson Family Cemetery rests inside this wrought iron gate.

It is more than a burial plot; it is a promise made.

And a promise kept…

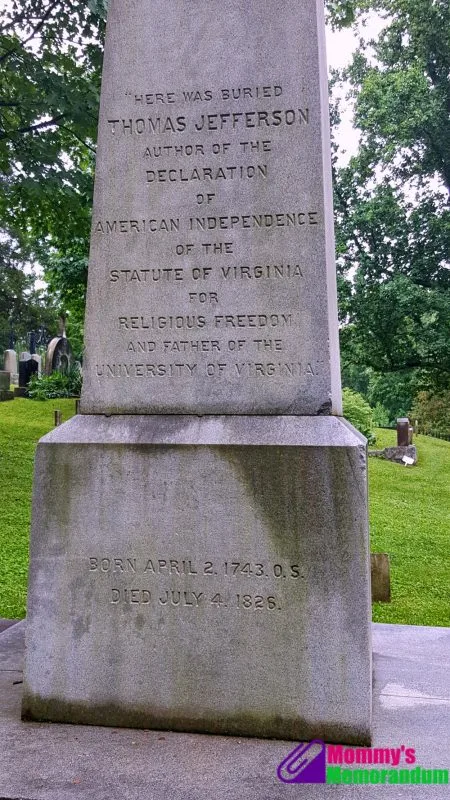

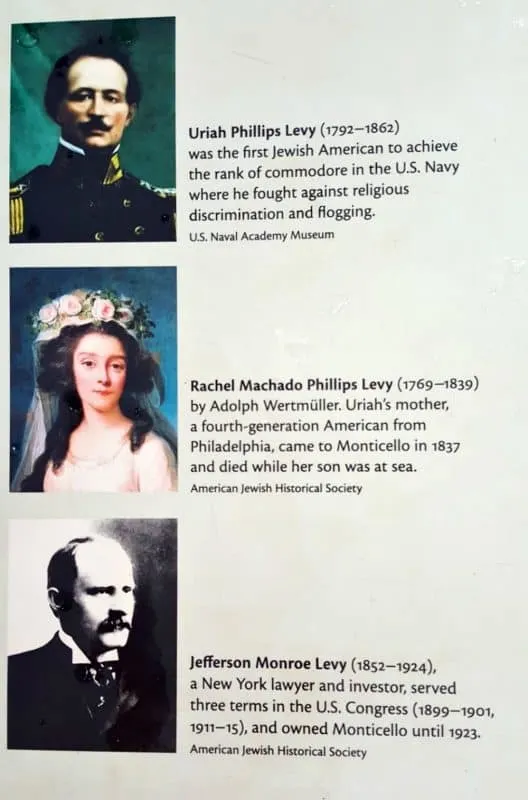

Looters chiseled away at his original tombstone designed by Jefferson. Uriah Phillips Levy, who purchased Monticello in 1836, moved the tombstone up to the house to protect it from further damage, and it was later taken by Thomas Jefferson Randolph to Edgehill for further safekeeping. The decision was made by Jefferson’s descendants to donate the original obelisk to the University of Missouri; it was unveiled at the University on July 4, 1885, and it now resides on the Francis Quadrangle.

A joint resolution of Congress in 1882 provided funding for a new granite monument, a tall obelisk, now locked up behind a wrought iron gate that displays his family crest.

It’s here, perhaps, we see the humility in Jefferson. He wrote his own epitaph, omitting from it mention of his presidency.

Miss M and I spot these two grave markers and think they are such a loving tribute to the people resting here.

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello Mulberry Row

The trail continues a little more, arriving at Mulberry Row. There are splendid views from here, and some of the finest woodwork in Virginia was made here at Joiner’s Shop.

The foundation and chimney are all that remain of the Monticello joiner’s shop. I find it to be one of the highlights of the trip.

The decades between my first visit and today taught me an appreciation for more of my surroundings. Now much older, I find his garden to be one of the most stunning gardens.

It sits about 250 feet southeast of the house.

It’s about 1,000 feet long and 80-feet wide.

It was cut out of a hillside and constructed by backfilling as a wall some twelve feet high as constructed.

There is a ten-foot wide path that runs the length of the garden along the edge of the retaining wall.

Perhaps Jefferson describes this area of Monticello best:

“I am constantly in my garden or farm, as exclusively employed out of doors as I was within doors when at Washington, and I find myself infinitely happier in my new mode of life”

The main part of the garden is divided into twenty-four growing plots that were arranged to which part of the plant was to be harvested.

Jefferson was very fond of English Peas and harvested them from early may until late August. There was even an annual neighborhood pea contest, whoever brought the first English pea to the table would host a dinner that included the winning dish of peas.

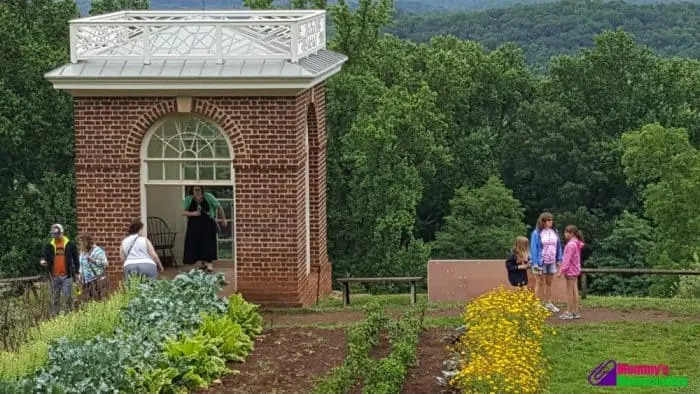

In the center, on the outer edge, a pavilion was built. It is where Jefferson sat to contemplate, to read, to enjoy the stunning view.

The brick pavilion is 13-feet 6-inches square and reflects similarities to the main house. It overlooks an eight-acre orchard of 300 trees, a vineyard, and Monticello’s berry squares, which are plots of figs, currants, gooseberries, and raspberries.

Two Italians, Filippo Mazzei, and Antonio Giannini contributed their experience and knowledge with fruit orchards. In 1774, Mazzei gave Jefferson apricot stones and 200 cherry pits, which were planted below the ridge where the vegetables were grown. Below the Garden Pavilion.

Beyond the “kitchen garden,” his plantation featured four satellite farms where Jefferson grew dozens of crops from corn and peas to clover and oats. He raised sheep, hogs, and cattle. For many years, his mills provided cornmeal and flour to the local area. For many years his primary crop on his four farms (Monticello, Shadwell, Tufton, and Lego) was tobacco until his research showed him the damage it did to the soil.

On the other side of Mulberry Row is the housing for the enslaved, free and indentured workers and craftsmen.

The pathway is lined with Mulberry and Sugar Maple trees. Thomas Jefferson had hoped for syrup from the Sugar Maples but found that it wasn’t cold enough here for them to produce maple syrup.

Uriah Levy’s mother Rachel is buried here on Mulberry Row also.

Archaeologists have discovered more than 1,000 artifacts here, and there are small signs that show what building was once here on this 400-yard row.

From home, this view of Mulberry Row is hidden.

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello:

Then you see it, the iconic home. You’ve seen it on the back of every nickel you’ve bartered and yet, here, in its presence, it takes on a new life.

I stand in the grass of Monticello.

I kick my shoe off and let the blades of the soft grass caress my feet. I imagine what it must have been like to have been welcomed here by Thomas Jefferson.

I stand to look at the view in awe of the magnificent backdrop it has played in history. The embrace he shared on that last visit General Lafayette paid to Monticello. The magistrates, Presidents, family, and friends that stood here. The time the British dragoons rushed the hill to Monticello during the Revolutionary War and Jefferson narrowly escaped. The death of his wife, four of his children, even his own death. It all happened right here.

If the mundane and historical moments don’t move you, the precious and details of the architecture surely will.

Thomas Jefferson officially named the two entrances the “East Front” and “West Front.” The latter is the “nickel view.”

Monticello is an artistic reflection of the local resources surrounding it. At a time when the brick was still mostly imported from England, Jefferson chose to mold and bake his own bricks with clay found on the property. He used lumber, stone and even manufactured the nails on site.

Front entrance to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello

The front and back of the home face northwest and northeast. They open to flat green laws. Each is highlighted by a long, narrow porch. Each porch showcases five wooden steps which descend to a lawn adorned with oval flower beds.

The lawn fades into forests topped off with views of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

There are flourishes attached to the home’s red brick structure adorned with white trim.

Three white columns support Monticello’s understated three-story-high rotunda, the first dome to be placed on an American home.

The front porch of Monticello features two very unique items.

One is the clock with only an hour hand.

The second is the Weather Vane on top of Monticello.

The weather vane is attached to a dial on the ceiling of the porch, making it easy for residence and guests inside the home to see the direction of the wind without stepping outside.

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello Where Jefferson Died

190 years ago, in his bedroom in Monticello, on the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, our countries third President, author of the Declaration of Independence, spoke his last words, “Is it the Fourth yet?”

John Adams, second President of the United States, Jefferson’s political adversary and friend died the same day. His last words: “Jefferson still lives.”

It was hearing these last words of two great men, that gave me cause to think. Most of us are hoping to live to see another birthday; however, these two men hoped to die on the birthday of the country they shaped.

Wandering the trails and seeing the views from Monticello inspires me. From every direction, there is a beauty. There is greatness–rivers that run to the ocean, mountains that lead North to South.

Monticello is what Jefferson himself called an “essay in architecture.” He built it, tore it down, changed it, and perhaps died without it be completed.

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and the Levy Family

About ten years after the former President’s death in 1826, Uriah P. Levy purchased Jefferson’s run down estate, that was almost in ruin. He began a long and costly program of renovation and restoration, including the purchase of an additional 2,500 acres adjoining the historic property.

After Levy’s death in 1862, his will directed that Monticello – the house and property – be left “to the people of the United States.”

The government declined the offer.

My Thoughts on Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello

One of our country’s forefathers followed his dreams so passionately. He died in debt. His children sold Monticello, his life’s work. The United States didn’t want it when it was left in Levy’s will. It took decades after his death for him to perhaps be realized for the sacrifices he made in shaping our country.

Monticello is the good and the bad.

It is the past and the future.

It is the old and the new.

It is a reminder to dream, to work hard, life full, remember the sacrifices and strive always to be happy.

“I am as happy no where else and in no other society,and all my wishes end, where I hope my days will end, at Monticello. Too many scenes of happiness mingle themselves with all the recollections of my native woods and fields, to suffer them to be supplanted in my affection by any other.” -Thomas Jefferson

I had to climb the hill to realize it.

Perhaps, the iconic house on the “little hill,” in the center of the state of Virginia is the story of a life well-lived, the man who penned our Declaration of Independence from a country that denied us all that Monticello represents.

On that “Little Hill” I stood in a place where history has been recorded, where tragedy has happened, mistakes have been made, freedom won.

I was inspired and my feelings conflicted.

With one last view of the rolling hills where they tree lines meet the sky, I head down the “little hill” known as Monticello, and I no sooner reach the bottom and want to return.